Why carbon capture means we will be paying off fossil fuel companies for centuries

The history of the UK's abolition of slavery holds important lessons about who foots the bill when it comes to righting wrongs

Just how can we ‘just stop oil’? While the build out of wind and solar continues apace, fossil fuels still generate 80% of total global energy. Rapidly unpicking coal, oil, and gas from industrialised societies is a huge technical and engineering undertaking. Perhaps even more challenging is that some of the world’s largest and most powerful corporations will need to leave fossil fuels worth trillions of dollars in the ground. What can help us tackle this challenge? In his recent book History for Tomorrow, social philosopher Roman Krznaric argues that we should look to the past because there are many examples of societies collectively solving similarly difficult issues.

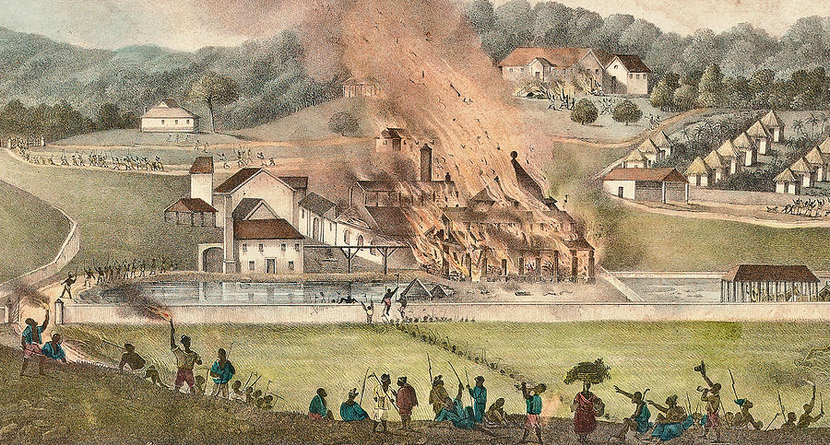

Take the abolition of slavery. It was the combination of gradual changes in laws and attitudes, combined with very sudden and sometime violent events that finally brought down the international slave trade. A pivotal moment was the Great Jamaican Slave Revolt of 1831 when 60,000 slaves rebelled in the British colony. While the slaves failed to win their freedom, the brutal suppression of the uprising by the British forces finally forced the government to rapidly act with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

From this very dark moment of British history comes a message of hope for rapid social change. It’s at this point in the story that Krznaric asks us to compare the behaviour of plantation owners of the 19th Century to the fossil fuel corporations of today. The argument that we must not rapidly phase out coal, oil, and gas are essentially economic. Yes, the exploitation of these fossil fuels may bring ruin to all eventually, but since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the five biggest fossil fuel companies have made a quarter of a trillion dollars doing just that. They argue that they must be given time to transition away to renewable energy systems or some other ways of turning a profit. Similarly, colonial plantation owners argued that they would need time to wean themselves off slaves. So while they could perhaps agree that there were good arguments for ending slavery, they implored the government to not act too fast. They suggested phasing slavery out over a number of generations.

However, if it is agreed that slavery is abhorrent, then it must stop. The abolition story as typically told has the UK Government finding its moral compass and immediately ending slavery in its colonies. A more accurate history is one in which the UK felt compelled to act because there were serious concerns that future slave revolts would mean not just loosing plantation profits but the colonies themselves.

There is another vital piece of this story that is often omitted, and it has an important message for today’s battle for climate justice. So let’s extend Krznaric’s analysis.

The UK Government addressed the economic concerns of slave owners by simply buying all their slaves. The Slavery Abolition Act that came into force in 1834 bought the freedom of some 800,000 enslaved people across the British Empire. This transfer of money from the state to slave owners represented around 40% of the nation’s entire annual budget. To pay for this, the government issued a series of bonds. This sort of government borrowing can persist well beyond the lifetime of any single government. In fact, it took 131 years for the government to pay back this loan. This means that I, along with all other UK taxpayers, were reimbursing colonial slave owners and their descendants until 2015.

The slaves themselves received no financial compensation. In fact some of them were compelled to continue to work on plantations for some years after 1834. It was the plantation owners who profited both from owning slaves, and then again when they were sold to the state. We can understand the relevance of this history by considering the amount of money governments funnel to fossil fuel companies today.

State subsidies of fossil fuels in 2022 amounted to $1.5trillion dollars. If you add in the environmental impacts of fossil fuels (very likely underestimated) then I, along with taxpayers around the world are paying the likes of Shell, BP, and Aramco over $7trillion a year to continue to wreck the climate.

These sorts of subsidies are increasingly including carbon capture and storage (CCS). For example, the UK Government recently announced £21.7billion of funding for the development of CCS projects across the UK. It is argued that some industries cannot rapidly decarbonise as this would make them uncompetitive and would threaten economic ruin. Instead, the carbon dioxide that is emitted during industrial processes such as cement production and glass making could instead be captured, transported, then piped deep underground.

Who would be key players in this new infrastructure? Why the fossil fuel companies of course, as they have the technological and engineering capabilities given their long experience of moving hydrocarbons around. It also so happens that they have vast reserves of methane gas which they claim can be used to generate hydrogen with CCS making it a zero emissions fuel. That there have been repeated failures of most of the major pilot CCS plants does not dampen the fossil fuel industry’s enthusiasm for all things CCS.

By positioning themselves as key players in CCS and also the direct removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, fossil fuel companies now seek to make profits from cleaning up the mess they are responsible for - profits increasingly underwritten by state subsidies and therefore our taxes. If, or rather when we pass 1.5°C of warming, then gigaton-scale carbon removal will be touted as the only way to get temperatures back down. This overshoot and correction approach to the climate crisis may require carbon removal to continue to operate for over three centuries.

UK citizens spent 131 years paying off slave owners. We are on course to reimburse fossil fuel companies for much longer. If we are going to learn from history, then this time there must be no rewards for bad behaviour. Polluters need to pay.