Thinking the unthinkable: climate overshoot demands a radical rethink of risk

Another week, another reflection on a workshop. This one was much more positive, even though it was about the end of the world.

I write on a train currently speeding through the German countryside on my way to Cologne where, hopefully, I will get a connecting train to Brussels, then the Eurostar to London, and then a train back home to Exeter. This week I have been in Hamburg attending a meeting of the Earth League. No, they don’t wear capes, but they do have some science super heroes like Kristie Ebi, Line Gordon, Johan Rockstrom, John Schellenhuber, Daniela Jacob, and Rachell Warren as members. One of the great privileges of academia is being able to spend time talking to very smart people. Getting past the imposter syndrome will always be a bit of struggle, but opportunities like this do not come up very often, and so fear of wasting it can be very motivating. What follows are my thoughts and observations - this is not a report on what was said, and any errors are mine alone.

A central topic of our conversation was overshoot - the now widely accepted idea that we are in the process of passing 1.5°C of warming and so overshooting the highest ambition of the 2015 Paris Agreement. What happens next? One answer is collapse. This is the ‘doomist’ answer. While I do not agree with arguments that conclude that collapse is now unavoidable, we cannot rule it out. That alone should be sufficient motivation to do everything we can to limit overshoot. Instead we are going backwards when it comes to climate action.

One possible reason for this - beyond the politics of Trump & co - is that the impacts of climate change are beginning to affect human societies in ways that make them less able to not only deal with these consequences, but degrades their abilities to tackle the drivers of climate change. Increasing climate shocks are already increasing food inflation in some places, wildfire and floods are destabilising other places, and in doing so producing more polarised politics in which climate action is rolled back.

We call such interactions a ‘doom loop’ and there is, in my humble opinion, a danger that these will rapidly increase with further warming resulting in the derailment of sustainability transition.

That’s not a cheery thought. What’s worse is that in some ways trying to manage these such risks represents the best outcome. Because things could turn out to be much worse. Let me paint a picture of this. My motivation to do so is not to upset you, depress you, demotivate you. I want to be as clear as I can be about what overshoot risks we are talking about.

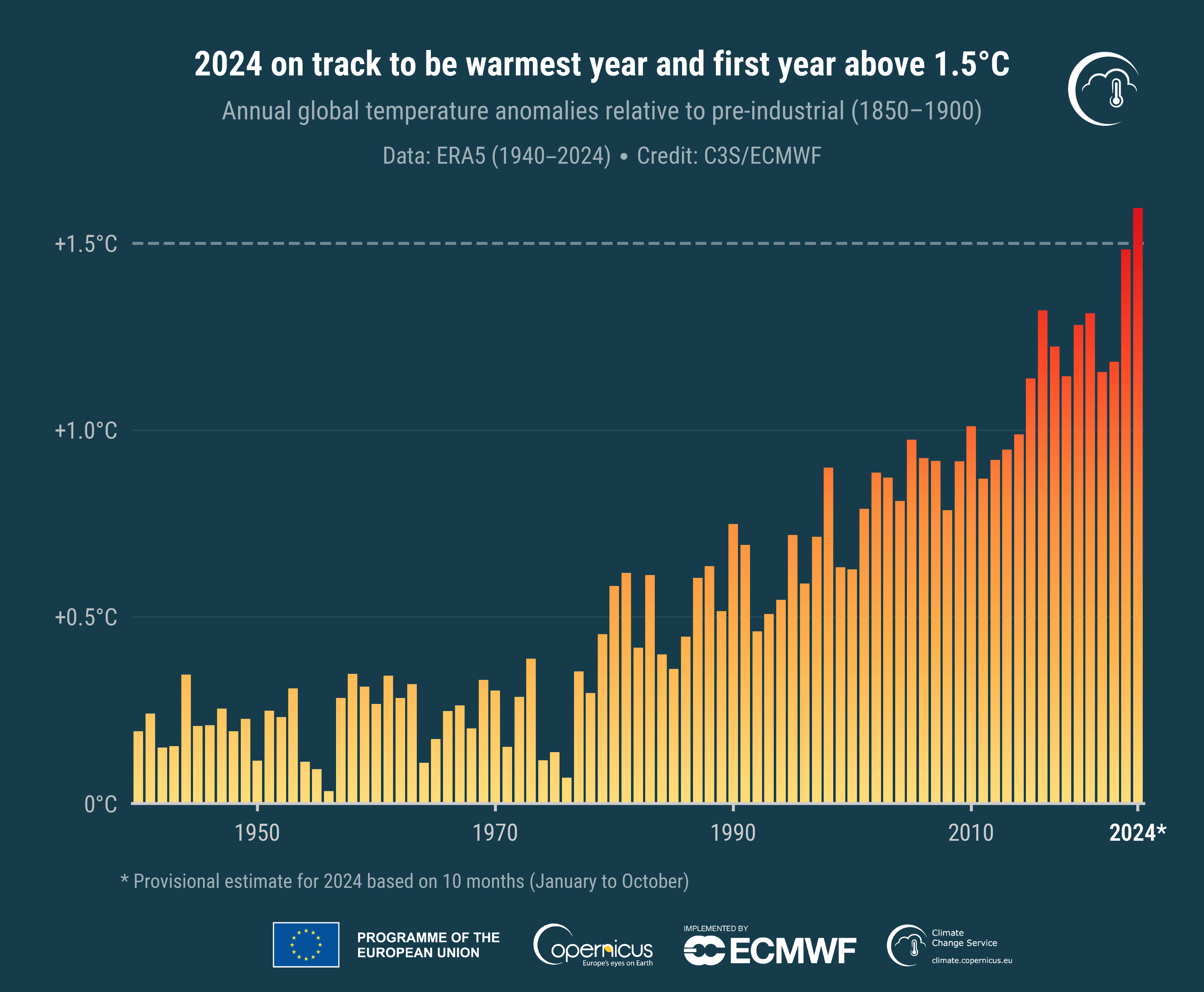

Figure from https://climate.copernicus.eu/year-2024-set-end-warmest-record

The increase in temperatures on land and sea in 2024 were extraordinary. While 2025 is not as epically hot, it is still much warmer than it ‘should be’. It is possible that we are witnessing an acceleration of warming as a result of changes in the Earth system. For example, the reflectivity of the Earth may be decreasing because of changes in cloud feedback, at the same time the ability for ecosystems on land to absorb carbon from the atmosphere may be degrading. If either of these two processes, in isolation or in some ways working together, strongly emerge then future warming may be much higher than central estimates.

You could then forget about trying to limit the overshoot to 2°C or 3°C. We may be on course to pass planetary thresholds towards a sort of hothouse that the Earth’s climate has not experienced for tens of millions of years. Along the way, vast oceans current systems like the AMOC would collapse, large regions of the Amazon would die back, vast ice sheets would melt with sea levels rising tens of meters. It would not necessarily be sudden. We are talking about changes that would unfold over decades and centuries. But along the way this gradual change in the Earth system would be punctuated with what would be extraordinarily violent and destructive events. This would mean collapse in the sense of the end of complex industrialised societies.

You may assume that climate policy is focussed on doing whatever it can to minimise such an outcome. A useful analogy is that airlines operate on very stringent risk assessments because the loss of an aircraft is a catastrophe - not just in human life, but because the costs involved and wider financial impacts could threaten the very existence of the airline. That along with very effective policies has resulted in commercial aviation being an extremely safe way to travel (such safety does not extend to those outside of the aircraft that have to suffer the air and noise pollution, nor the wider climate impacts from burning kerosene).

Unfortunately that is not the approach we are taking when it comes to climate risks - at all. Another transport analogy better captures the reality of our situation. The Ford Pinto was a small, cheap affordable car manufactured by Ford in the early 1970s. Unfortunately, design flaws made it extremely dangerous (the fuel tank was likely to rupture if rear ended and doors could be jammed shut). Tens of people burnt to death in these cars. There was eventually a series of court cases which culminated in Ford being found liable for million of dollars of damages. These financial penalties were so high because the court determined that Ford knew about these design flaws but concluded that it would be cheaper to pay individual injury and fatality costs, than recall the cars and fix them (if that sounds familiar then perhaps you are remembering that scene on the plane in Fight Club).

While politicians may proudly proclaim that they have signed up to ‘net zero by 2050’, what they are actually motivated to do is to minimise the economic impacts of climate change. This has two components: first, the destruction and death and so economic damage caused by further warming - this is like the number of people hurt and killed in those deathtrap Ford Pintos; second, the costs of rapidly decarbonising - think of all the capital expended on fossil fuel infrastructure that will need to be repurposed to zero carbon alternatives - this is like the costs of recalling and fixing all the lethal cars.

In the climate context, the first set of risks are typically called climate or physical risks, the second are transition risks. Optimal policy seeks to find the rate of decarbonisation that results in balancing the two risks. My argument has been that this completely misses derailment risks - societies may be much more vulnerable to climate change because it impedes our ability to deal with existing threats, and stops us from managing future risks. As impacts increase and societies are less able to deal with them, societies are also less able to continue sustainability transitions - in fact such efforts could become completely derailed.

The result of all this, is that the deeper and longer we overshoot into dangerous climate change, the greater derailment risks become and so the greater the risks of us passing further into the climate storm. At the moment, overshoot is presented as some sort of anomaly, a blip on the road of never-ending economic growth, development, and ‘progress’. The proposed solutions are technocratic and centre on large-scale carbon dioxide removal which is supposed to magically appear at some point as a result of innovation and necessity.

I often find myself in meetings getting increasingly frustrated, and to be honest about it, increasingly freaked out at how wildly complacent everyone else seems to be about overshoot risks. That’s why this week’s interactions were so positive for me. Everyone there was fully aware of the extraordinary reckless gamble we are taking on the future, and what is urgently needed now in order to reduce risks. We’ve had enough wishful thinking and hand waving about future technological salvation when it comes to the climate crisis.

Seriously examining how bad things may get is not doomist or defeatist. It’s not giving up, but getting real about the task at hand.