Living beyond limits

Decades of climate policy failure means we must find ways to live in a more dangerous world

Given the rapid rise of AI generated content, one can no longer be sure that an online video is legit. New algorithms are able to produce content that is extremely difficult to tell apart from real footage. So my first thought when I watched a video of a blaze breaking out within COP30 – the latest international climate conference in Belem, Brazil - was this must be a fake video trying to make some sort of metaphor about politics and planet being on fire.

Not so. On Thursday a fire did start within the pavilion which rapidly developed into a frightening inferno. While some people were treated for smoke inhalation, fortunately no one was seriously harmed. That’s despite some people rubber necking and taking videos with their phones thus getting in the way of people who were desperately running around with fire extinguishers. Again, another metaphor for the climate crisis.

As the conference comes to a close we now enter the obligatory phase of recriminations, resignation and endless reactions to what will, again, prove to be grossly insufficient. You can see the details of the agreed text unfolding on the COP30 website. My current understanding is that this won’t even mention the phase out of fossil fuels which means that most of what follows risks being entirely irrelevant. If we can’t phase out coal, oil, and gas quickly then we are cooked.

COP30 comes ten years since the world’s leaders gathered in Paris for the 21st United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21). The surprising outcomes of two weeks of intense negotiations was the Paris Agreement, and its objective to limit warming to well-below 2°C. That was a major increase in ambition, but in important respects represented the minim required because beyond 1.5°C of warming some low lying island nations states would cease to exist being submerged by rising seas.

For the Paris Agreement to have any chance of success, governments – particularly those in rich, industrialised nations - would have needed to accelerate the phase out of fossil fuels at the same time of phasing in the financial support for energy transitions in the Global South. Neither happened. In 2024, industrial processes poured a record-breaking 37.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, while the amount of climate finance thus far promised is a fraction of what is needed.

The available carbon budget for a 50% of limiting warming to 1.5°C will be gone within a few years, perhaps already is gone. We are heading into overshoot. The world is going to become more turbulent and more dangerous. What next?

Responding to that question was one of my key motivations in working on a project with the Earth League, an international organisation that provides scientific insights on change and transformation within the Earth system and informs decision-making for global sustainability. One result of this is a paper recently published in the journal One Earth: Living beyond limits: Consequences of missing the decisive decade for preserving our planet’s life-supporting systems. What follows are some of my thoughts and reflections about. I’ve not discussed this with my co-authors, and I am solely responsible for any errors and omissions.

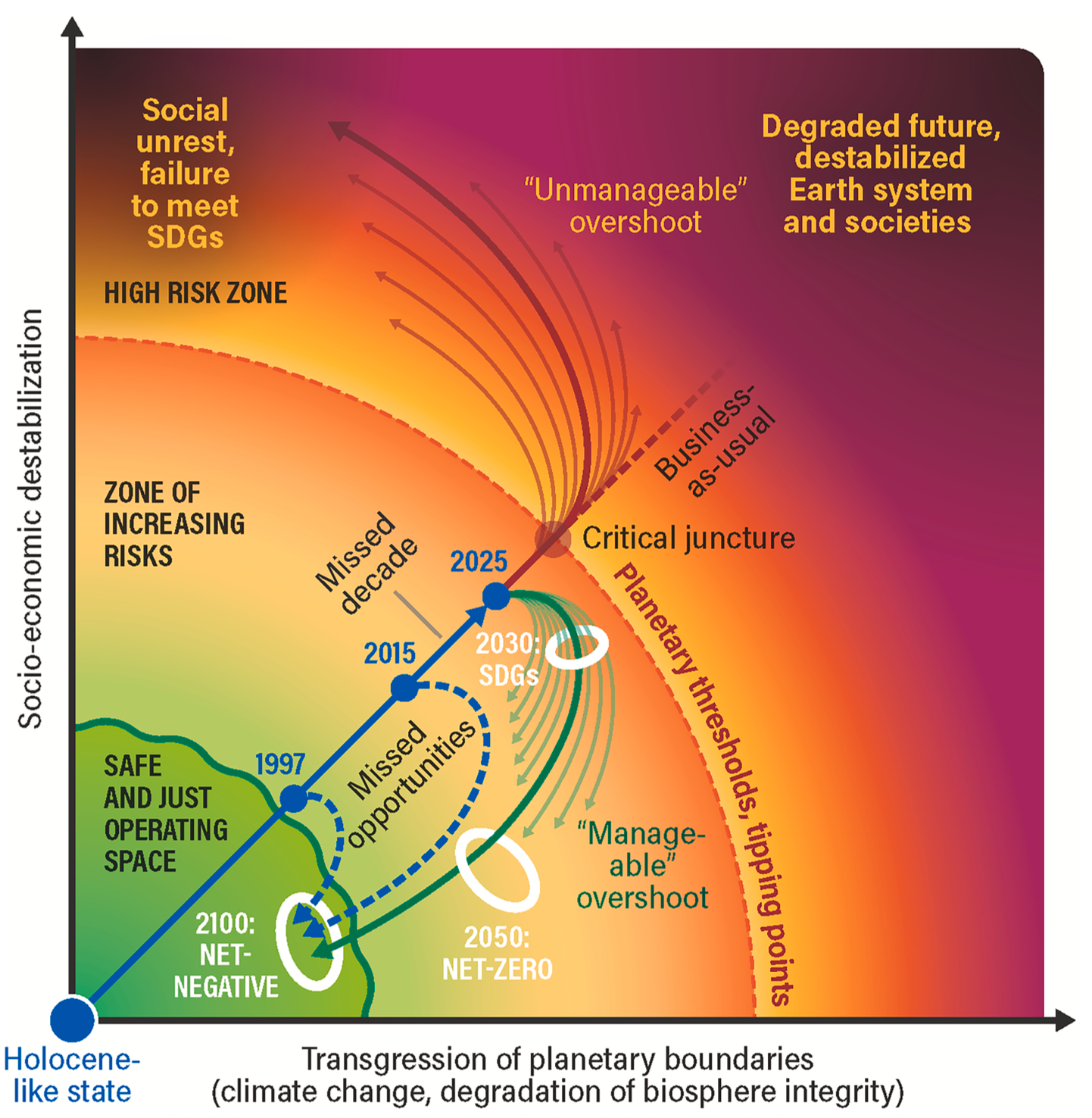

Below is the key figure of the article. This shows how far we are into the danger zone of climate change. The missed opportunities up to 2015 are the failures of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to bend the global emissions curve. There then followed a missed decade since the Paris Agreement. Significant impacts are now unavoidable. Increasingly destructive storms will produce more loss and damages, more loss of life. But the scale of suffering is still very much up to us because how fast we phase out fossil fuels and the phase in of desperately needed climate financing are the crucial factors in determining how vulnerable societies will be to environmental change. We are now heading towards a critical juncture. This can be understood as an amount of environmental change that will fundamentally unpick the life-sustaining feedback loops of the Earth system.

What does “Living beyond limits” mean? Johan Rockstrom has lead the development and application of the planetary boundaries framework since 2009. The original paper argued that humanity was driving the Earth system out of a safe space of the Holocene epoch in which all of civilisation have emerged. Since then the situation has become worse with more climate change, more biodiversity loss, more land use change, more disruption of biogeochemical flows, and more novel chemical entities. When it comes to considering limits, we could go back much further to the 1972 seminal book Limits to Growth which (in)famously concluded that industrialised societies were on course to collapse as the result of dwindling resources and saturating pollution sinks.

Over half a century on, the challenge is not to avoid limits, but to work out how to live beyond them. The way we put it in the article is:

A decade ago, science showed us a narrow window of opportunity to avert the looming planetary crisis. That window has closed. We are now in the midst of the storm, and the situation demands an acceleration of existing efforts while exploring new avenues for action.

So our article does not just say we are on course to breach limits, but instead centres the vital issue of how can we best deal with and respond to the brutal reality of passing them. Here, some people may argue there isn’t really much of a question to answer because going beyond limits means collapse. That’s possible. But I still see no evidence that this outcome is unavoidable. It seems reasonable to me to try to explore all alternative pathways.

Charting a course into the future means we must acknowledge past failures. The second part of the title is “Consequences of missing the decisive decade for preserving our planet’s life-supporting systems”. There is still a very large disconnect between what politicians are saying about the climate crisis and the reality of the situation. For example, the cry of “1.5 is still alive!” was still ringing out from within COP30. While well intentioned, this completely misrepresents the situation. 1.5 is long gone. But this doesn’t make 1.5 irrelevant. I’ve never understood the argument that we must refuse to accept 1.5 is lost because it will undermines efforts to limit further warming. What we do matters more the warmer it gets because climate impacts may be strongly non-linear, and so further warming will have disproportionately more destructive consequences.

Unfortunately one response to this challenge is to invoke technological magical thinking. Overshoot is presented as a temporary exceedance of 1.5°C or warming that we can recover from with geoengineering in the form of large-scale carbon dioxide removal and solar radiation management. The lure of such an approach of course is that it does absolutely nothing to challenge the political and economic systems that got us into this mess. More to the point it may not work, and indeed risks making the situation even worse.

We argue that a more robust and credible would have the following two elements:

(1) a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels alongside a scale-up of renewables to prevent an energy shortfall; (2) a transformation of the food system from a net carbon source to a sink, while protecting biodiversity and meeting global nutritional needs for a growing population

We also must help Earth and social systems recover resilience. There is increasing evidence that vital carbon stores such as forests are beginning to leak carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. At the same time crucial social institutions are crumbling in the face of a constant barrage of misinformation, and other mechanisms of climate denial and delay. In many ways, the task we face is much harder than it was a decade ago. But that does not make it any less urgent. At risk of invoking the sort of technocentric rhetoric that too often accompanies discussions about overshoot I will end with some words from John F Kennedy. These are from his famous 'moon speech' of 12th September 1962 in which he committed the United States to landing on the moon before the end of the century.

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

We must choose the Earth simply because we have nowhere else in the universe to go. This will be greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. If we are to overcome this challenge then we must confront the stystemic drivers of climate change and overshoot of other planetary boundaries. The most precious resource to such ends is the capacity to imagine a different world, and the ability to link that to people's lived experiences. This should not be impossible: there are endless ideas about how to live more in balance with the Eath and in ways that would dramatically improve the wellbeing of the vast majority of humanity.

Ten years on from Paris Agreement we can say it has failed. We are at the end of the beginning in the battle for a liveable future. Where we go next is still very much up to us.