It’s the end of the world as we know it

A hotter more dangerous world demands new thinking about the climate crisis

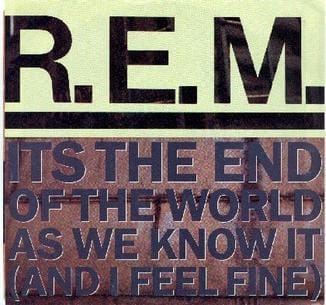

Recently I’ve been DJing at events and playing R.E.M.’s It’s the end of the world as we know it (and I feel fine). Most people in the crowd have either never heard it before, or think of it as a bit of retro their parents have in their playlist. In any event, I can sometimes get them singing the chorus “It’s the end of the world as we know it… and I feel fine”. When it really works it becomes a cathartic howl.

I mention this because as warming passes beyond 1.5°C people are quite understandably asking what’s next? If the supposed highest ambition of the 2015 Paris Agreement isn’t going to be met (in fact we seem to be on course towards a 3°C warmer world) then is it over, is this the end of the world? There are numerous threads to pull out from that question. In the future I will write about how to find the rubies in the rubbish of doomism, and related to that geoengineering and how 1.5°C has become something of a battlefield over which competing narratives around carbon removal and solar radiation management are being fought.

Here I want to dig into the reticence to talk about warming beyond 1.5°C. There are lots of compelling reasons to not declare 1.5°C is over. For example, giving up on 1.5°C will immediately be used by fossil fuel interests to argue that rapid decarbonisation should not be pursued. In 2022 I was told by someone attending COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt that my writing was being circulated by oil and gas states as evidence that scientists say 1.5°C is impossible and so we should be looking at the much more ‘realistic' threshold of 2.5°C. Tempted as I was to be flattered that I was having some sort of impact on international climate negotiations, I think the reason this person reached out to me was that they were increasingly frustrated at what was going down in the negotiations and were rather unimpressed with some of the things I had been saying about net zero.

All that said, I get it. Signalling that 1.5°C is no longer possible will add momentum to attacks on any meaningful climate action. But this does’t make it not true. For a while I tried to argue that saying we are passing 1.5°C should increase climate action. If your house is on fire and has progressed to the point of gutting your living room, you don’t give up. You fight the fire harder. Such reasoning proved to be about as effective as throwing a bucket of water onto an actual inferno. It quickly flashes to steam and disappears.

I have since come to realise that some of the reticence to simply acknowledge the facts about warming beyond 1.5°C comes from what is essentially an inability to see past the Paris Agreement. The climate centrist circle finds it impossible to acknowledge 1.5°C is over because it cannot acknowledge the Paris Agreement has failed. It can’t do that because it finds it impossible to question the net zero approach it is built upon. In a very literal sense it cannot imagine another response to the climate crisis. They truly do believe there are no alternatives, and so are resigned to lashing themselves to 1.5°C even as it disappears under the surface.

Heroic as that may be, my frustration with this has been that when warming passes 1.5°C, people will understandably want to know what next. If we don’t come up with compelling narratives about post-1.5 futures, then fossil fuel interests will and we won’t like them. This is what we are now seeing.

The worse climate change gets, the more loss and damages it produces, the more people it kills, then the more policy makers will respond with serious efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Ultimately a sort of self-regulating or negative feedback loop will emerge that would stabilise emissions. That sounded like a reasonable assumption. Unfortunately, it’s proved to be dangerously wrong.

Just as we are realising that the risks of climate change may have been vastly underestimated, we are seeing a reduction in political and industrial ambition on climate mitigation. Not only that, in the US we are seeing efforts to destroy the science that underpins our understanding of how the climate works and what humans are doing to it. This can - admittedly simplistically - be understood as vested fossil fuel interests doing whatever they can to insulate their wealth and power from the consequences of climate change. If the passengers of the ship are starting to get restless because they can see they are steaming straight towards a massive storm, then simply turn off the radar, pull down the blinds and show the latest reality TV episode. Any feedback loop is short circuited and so emissions can continue.

Beyond the crazed behaviour that comes from the idolatry of coal, oil, and gas, there is a wider form of denial motivating this behaviour. Most people would find the prospects of climate breakdown horrific. It’s not such a big step from finding something intolerable to unimaginable; it’s just so terrible it cannot happen. One way out here, is to assume that we will avoid catastrophe by essentially coming to our senses and quickly phasing out fossil fuels at the same time as increasing deployment of renewables. Net zero augments that with a belief in future large-scale carbon dioxide removal technologies.

Climate centrists are fond of repeating statements such as: scientists say that to limit warming to well below 2°C, we must be removing one hundred million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year by the middle of the century This is the overshoot scenario. Arguably, the Paris Agreement bakes in overshoot with its 2100 targets and talk about sources and sinks of carbon. I will write more about this in the future, in the meantime here is Robert Watson’s, Wolfgang Knorr’s and my thoughts about it, and here is Wim Carton’s and Andreas Malm’s excellent book on the topic. My point now, is that the necessary condition of removing vast amounts of carbon for 1.5°C does not have any bearing on whether this is actually possible. Beginning statements with ‘scientists say’ is an appeal to authority, an attempt to suggest this is an objective and reasoned conclusion rather than desperate wishful thinking.

So if we are indeed passing 1.5°C is this the end of the world? If you mean the collapse of civilisation then no. But we are witnessing the end of the net zero world view. Net zero was developed at a time when dangerous climate change could still be averted; carbon emissions could be progressively decoupled from industrial activities; global economic growth could continue it’s exponential reach for the skies. In short, the transformation to sustainable societies while daunting, indeed unprecedented, was potentially achievable within the bounds of current political systems. If we can still see such a world, it’s only in the rear mirror.

Things are going to get worse. Rising temperatures, rising conflict over resources, rising forced displacement and migration. Rising sea levels are perhaps the least of our concerns when you consider how climate impacts can cascade across societies. These are the sorts of reinforcing feedback loops that have the potential to rapidly amplify the destructive biophysical consequences of climate change. Climate policy needs to be able to function in this world. Understandably, there is increasing interest in climate adaptation (in places read that as a desperate scrabble to try to protect capital). What we have yet to see is a serious attempt at making climate policy itself adaptive and resilient to a much more dangerous world.

It’s the end of the world as we know it. Continuing to cling onto the net zero approach of the Paris Agreement is to be in denial about what is happening, and what this new world demands. It’s not fine.