Climate tipping points should not be used to justify geoengineering

We are at a fork in the road. Crossing the first global tipping point should not be an excuse to lock in geoengineering, with its empty promises and spiralling risks.

This is the original text of an article to be translated into Spanish and published in the annual edition of Climática, a magazine specialising in climate and biodiversity

Greenhouse gas emissions are at all-time highs. The ten warmest years ever recorded by humans have all occurred within the last decade, with 2024 being the hottest ever. And now, the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report has found that warm-water coral reefs are unable to recover from bleaching events. The first Earth system tipping point is being crossed and as temperatures continue to rise, other tipping points will be activated. What may follow is the disintegration of the Thwaites “Doomsday” glacier leading to major sea level rise, or the collapse of ocean currents crucial for European weather systems. Governments, academia and industry are scrambling to respond and many are placing bets on technological solutions. Enter geoengineering – once a niche idea, now a multi-million dollar research and policy topic.

Geoengineering is the deliberate interference in the Earth system intended to reduce the harmful impacts of climate change. The various methods are generally classified under two headings – solar radiation management and carbon dioxide removal. It was the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, a huge Indonesian volcano, that is often cited as the key inspiration for the former. Pinatubo spewed millions of tons of sulphur into the upper atmosphere, which bounced some of the sun’s energy back into space. Global average temperatures decreased by around half a degree centigrade for a couple of years. Could humanity reproduce this natural cooling?

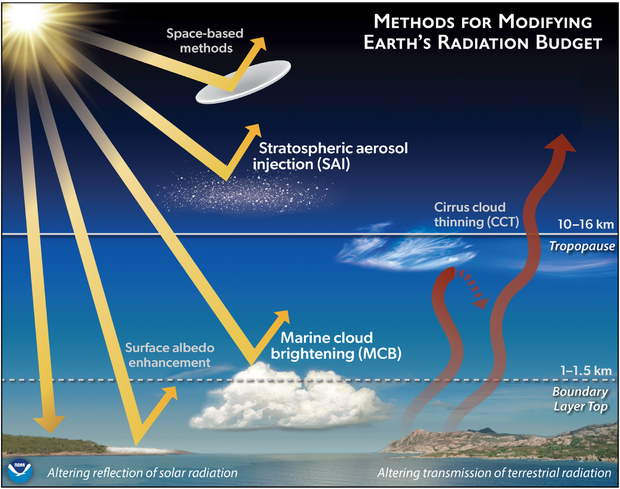

Proposals for artificial climate cooling exist at all levels of the Earth system. The most popular idea is for modified commercial airplanes to spray sulphates into the stratosphere. Other suggestions include covering deserts in reflective materials, spraying seawater into clouds to enhance their brightness, and even launching country-sized sunshades in space, to orbit a literal astronomical 1.5million km from the Earth.

At best, solar geoengineering is a sticking plaster because it does not reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. Carbon dioxide removal technologies do, and schemes range from nature-based approaches focused on forests and soils, to highly speculative industrial processes such as direct air capture, which would suck carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere.

However, all geoengineering approaches carry risks. For example, high reliance on tree planting can significantly impact food and water security, and biodiversity. Ocean-based approaches can negatively affect ecosystems. Marine cloud brightening could lower temperatures in certain regions but could cause negative side effects elsewhere due to links in the global climate system. Large-scale stratospheric sulphate injection could cause havoc with the monsoons in the Global South. Even if this particular technology worked as intended, increasing reliance on it would create the risk of ‘termination shock’. This would be the rapid and devastating rise in global temperatures if this artificial cooling were to be stopped without significant amounts of carbon dioxide removal having taken place.

Relying on profit-driven market solutions for carbon removal raises the spectre of corruption. Whilst solar geoengineering has not yet been seriously commercialised, there is a distinct lack of transparency in how the research is funded and trialled. There is also the prospect of nations treating solar geoengineering not just as a climate issue but one of national security, given the risk of devastating regional impacts and consequently the risk of counter-geoengineering.

Geoengineering is often publicly framed as a necessary and humanitarian response to the climate crisis, but the hidden motivations of its advocates and funders should be carefully examined.

In the race to find climate solutions which do not require any brakes to be put on economic growth, you may think that Big Oil is the frontrunner. Surprisingly it’s Big Tech that is dominating this space. Microsoft in particular is super-charging the sector, having spent around $8bn on carbon removal credits in the past few years and millions more on separate investments in carbon removal suppliers. Microsoft’s interests in geoengineering may be purely financial. There are potentially large returns from being an early investor in what could become a trillion dollar voluntary carbon market. Their actions could also be driven by more strategic considerations. Big Tech’s carbon emissions are soaring due to the accelerating build of vast data centres which are in part being driven by the AI boom. Promising to remove carbon emissions could prevent deep scrutiny of sustainability strategies and help evade tighter environmental regulation.

The problem is that the virtual market for carbon credits currently has no discernible impact on the very real atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide. It’s here that geoengineering proponents will ask us to keep faith with technological innovation - scaling up carbon removal technologies will of course take time, but the ability to remove billions of tons of carbon dioxide is within our grasp. In order to buy humanity time, we could deploy solar geoengineering as an emergency climate fix. But the risks are immense and who will benefit is uncertain.

We all know that tackling the root cause of climate change – the burning of fossil fuels – is essential. If we do not rapidly shift away from a fossil-fuelled global economy we face disaster, something that vulnerable communities and ecosystems worldwide are already experiencing. The good news is that we have the technological and social infrastructure to rapidly phase out coal, oil and gas, and replace the economic and political power bases they have created.

Unfortunately, it is these power bases which are delaying the sustainability transition. The institutions, corporations and billionaires who have benefitted from the riches and influence that fossil fuels have delivered, are resisting the pivot towards more equitable societies. Rather than entertain any idea of redistributing power and wealth, they are instead hoping that geoengineering technologies will achieve twin goals – being not just climate saviour, but also torchbearer for continued and accelerated economic growth.

We are at a fork in the road. Crossing the first global tipping point should not be an excuse to lock in geoengineering, with its empty promises and spiralling risks. Instead, it should be the moment we pivot towards a fundamental shift in thinking and action about our societies, economies and politics. A safer but also more equitable climate future is possible.